The Human Body is truly remarkable. Designed and built for movement, the body is tough and resilient. It adapts to the various demands or environments that it is subjected to. If your environment is active, it adapts to the specific load, type, or pace of the activity by increasing strength and/or endurance. If your environment is sedentary, it adapts by decreasing strength and endurance, and stores the unburned energy as fat. Thus, good or bad, your body adapts to the lifestyle that you subject it to, meaning your actions or inactions really do matter!

| Fitness: Basic Training |

- Basics Defined:

- Physical Fitness:

- The ability to perform daily tasks vigorously and

alertly, with energy left over for enjoying leisure time

activities and meeting emergency demands (President's

Council on Physical Fitness and Sport)

- Fitness can be described as a condition that helps us look, feel and do our best; it is the foundation for health and well-being.

- The ability to perform daily tasks vigorously and

alertly, with energy left over for enjoying leisure time

activities and meeting emergency demands (President's

Council on Physical Fitness and Sport)

- Physical Activity:

- Any Body Movement carried out by your skeletal muscles and requiring energy.

- Exercise:

- Planned, structured, repetitive movement of body body designed to improve or maintain physical fitness.

- Physical Fitness:

- Health-Related Components of Physical Fitness:

- Cardiorespiratory Endurance:

- Ability of the heart, lungs and vascular system to deliver oxygen-rich blood to working muscles during sustained physical activity.

- Cardiorespiratory Endurance:

- Muscular Strength:

- Amount or degree of force that a muscle can exert.

- Muscular Endurance:

- Ability of a muscle, (or a group of muscles), to withstand stress, hold a particular position, or contract repeatedly for an extended period of time.

- Flexibility:

- Range of motion that a limb has around a fixed point (joint).

- Body Composition:

- The relationship or makeup of lean body mass (muscle, bone, vital tissue and organs) to fat mass.

- Considered to be more of an accurate measure of physical fitness levels than the BMI (Body Mass Index).

- Understanding Basic Fitness Principles:

- The keys to selecting the right kinds of

exercises for developing and maintaining each of the basic

components of fitness are found in these principles:

- Principle of Overload

(or Overload Principle):

- To do more than the body is

accustomed to; to apply more stress, repetitions, or range

of motion than a muscle or joint is accustomed to.

- Types of Overload:

- Aerobic Activity:

- Meaning "with oxygen" or "in the presence of oxygen".

- Continuous and rhythmic (moderate) activity (using larger muscle groups) for a sustained period of time.

- Does not cause a participant to be out of breath.

- Aerobic Activity:

- Types of Overload:

- To do more than the body is

accustomed to; to apply more stress, repetitions, or range

of motion than a muscle or joint is accustomed to.

- Principle of Overload

(or Overload Principle):

- Anaerobic Activity:

- Meaning "without oxygen" or "in the absence of oxygen"

- Short strenuous bursts of high intensity activity that use oxygen faster than your body can replenish it; such as sprinting or explosive weight training.

- Causes participant to be "out of breath"

- The keys to selecting the right kinds of

exercises for developing and maintaining each of the basic

components of fitness are found in these principles:

- Static Stretching:

- Meaning "constant" or "continuous"

- Stretching or elongating a muscle to a point of "tightness" and holding for a period of time.

- Dynamic Stretching:

- Controlled movement of body parts, gradually increasing range or motion, reach, and/or speed of movement.

- Example: controlled leg or arm swings that take you gently to the limits of your range of motion.

- Isotonic Movement:

- Muscle contraction with movement

- Isometric Movement:

- Muscle contraction without movement

- Principle of Specificity:

- Training approach used by competitive athletes.

- Training of specific muscle groups and movements used in a particular sport or activity.

- Principle of Regularity or

Consistency:

- Exercise must be ongoing, on a regular or consistent schedule for the body to adapt and benefits to occur.

- At least three to five balanced workouts a week are necessary to maintain a desirable level of fitness.

- Principle of Progression:

- To increase (or progress) the

intensity, frequency and/or duration of activity over

periods of time in order for "overload" to occur and

improvement to take place.

- Progressive Resistance Exercise

(PRE)

- Placing Increasing Amounts of

Stress on your body will cause adaptations that

improve fitness.

- Placing Increasing Amounts of

Stress on your body will cause adaptations that

improve fitness.

- Periodization:

- Planned Variations in your exercise that cumulatively improve your fitness and performance, while reducing the plateau effects of training.

- It strategically manipulates the fitness principles to optimize training.

- Progressive Resistance Exercise

(PRE)

- To increase (or progress) the

intensity, frequency and/or duration of activity over

periods of time in order for "overload" to occur and

improvement to take place.

- Principle of Recovery:

- A period of rest or recovery for

muscle groups that have been through an intense

(normally strength training) bout of exercise. Can be

accomplished by:

- A day of rest or an easier training day.

- Alternating muscle groups

- A period of rest or recovery for

muscle groups that have been through an intense

(normally strength training) bout of exercise. Can be

accomplished by:

- Principle of Reversibility:

- A person loses the effects of training when they stop working out; the physiological effects of fitness training diminish over time, causing the body to revert back to its pre-training condition.

- F.I.T.T. Principle, the Foundation of Exercise:

- Frequency

- How often you should workout.

- Example: 3 to 5 times per week.

- Intensity

- How hard you should workout each session.

- Example: Workout performed at 70% of my maximal heart rate.

- Time

- How long should each workout session be.

- Example: Each run is 20 minutes long.

- Type

- The Type of activity you are performing.

- Example: I will be walking on the treadmill to improve my fitness

- Frequency

- Benefits of Regular Physical Activity:

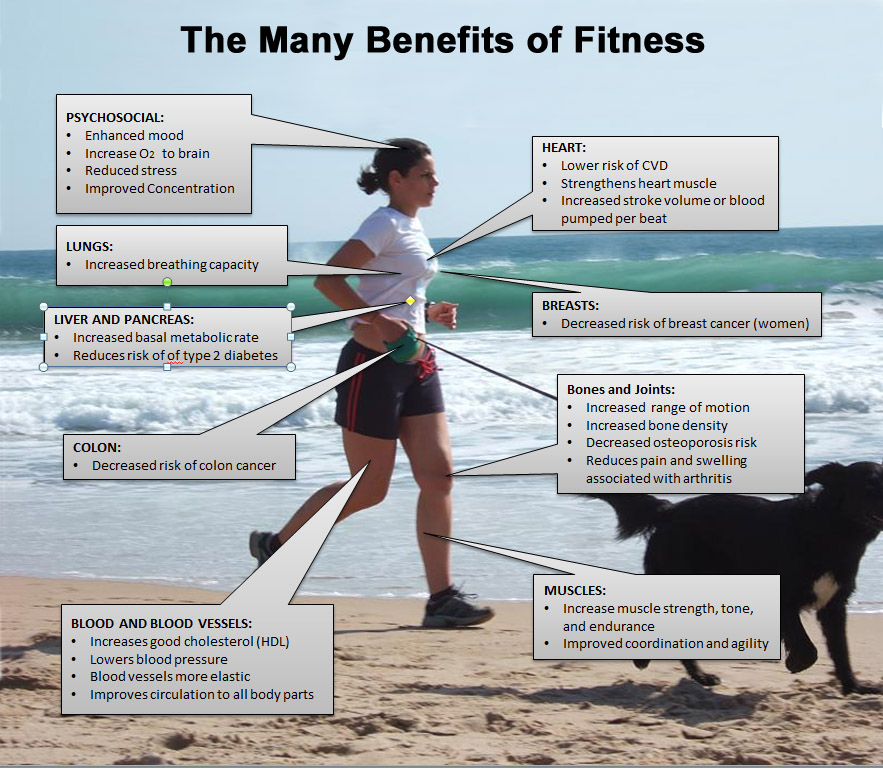

- Regular physical activity can change your life, and has been shown to improve more than 50 physiological processes of the body.

- The illustration below outlines a few of the major benefits of ongoing, regular exercise.

- Major Barriers to Physical Activity and Fitness:

Convenience and technology have made our lives much easier and less physically demanding However, these are also key reasons for our catastrophic obesity numbers. With school, work, family and friends, there are a multitude of factors that can affect our plans to become more physically active. Understanding common barriers to physical activity and creating strategies to overcome them may help you make physical activity part of your daily life. Consider the following barriers and alternatives from the US Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Physical Activity for Everyone, Making Physical Activity Part of Your Life:

- Lack of Time:

- Identify available time slots. Monitor your daily activities for one week. Identify at least three 30-minute time slots you could use for physical activity.

- Add physical activity to daily routines; walk/bike to school or work, organize school activities around physical activity, walk the dog or child, exercise while watching TV, park farther away from your destination, etc.

- Select activities requiring less time, (walking, jogging, or stair-climbing).

- Lacking Self Confidence or Social Support:

- Explain your interest in physical activity to friends and family. Ask them to support your efforts.

- Invite friends and family members to exercise with you. Plan social activities involving exercise.

- Develop new friendships with physically active people. Join a group or class at school.

- Lack of Energy (too tired):

- Schedule physical activity for times in the day or week when you feel energetic; for some this is early mornings, for others it is later in the day.

- Convince yourself that if you give it a chance, physical activity will increase your energy level; then, try it.

- Lacking Self-Motivation:

- Find a workout partner for co-motivation.

- Make physical activity a regular part of your daily or weekly schedule and write it on your calendar (three weeks is habit forming).

- Enroll in an exercise class at school.

- Exercise is Boring:

- Cross-train; mix and match different activities daily to change the landscape.

- Take a class to develop new skills for variety; yoga, dance, Pilates, etc

- Workout to your favorite music

- Two Left-Feet (lack of skill):

- Select activities requiring no new skills, such as walking, climbing stairs, or jogging.

- No Resources:

- Select activities that require minimal facilities or equipment, such as walking, jogging, jumping rope, or calisthenics.

- Identify inexpensive, convenient resources available in your school or community (non-credit programs, park and rec, worksite programs, etc.).

- Fear of Injury or Getting Hurt:

- Learn how to properly warm up and cool down.

- Learn how to exercise appropriately considering your age, current fitness level, skill level, and health status.

- Search for activities that involve minimal risk.

- Weather:

- Develop a "rainy day" plan, including activities that are always available regardless of weather (indoor cycling, DVD workouts, indoor swimming, calisthenics, stair climbing, jumping rope, mall walking, etc)

- Family Duties:

- Trade babysitting time with a friend, neighbor, or family member who also has small children.

- Go for a "stroll-er" with your little ones.

- Exercise with the kids; go on walks, play tag or other running games, get an aerobic dance or exercise DVD for kids and workout together.

- Jump rope, do calisthenics, ride a stationary bicycle, or use other home gym equipment while the kids are playing or sleeping.

- Try to exercise when the kids are not around (e.g., during school hours or nap time)

- Be creative and schedule it in!

- Muscle Soreness and

Exercise:

- One of the not-so-kind byproducts of an exercise program are sore muscles.

- Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness

(D.O.M.S.):

- Any activity that places an unaccustomed load on muscles may lead to a condition referred to as delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS).

- This type of soreness is different from acute pain or soreness that develops during the actual activity.

- Typically, delayed soreness begins to develop 12-24 hours after the exercise has been performed and may produce the greatest discomfort between 24-72 hours after exercise.

- The soreness that you feel is actually muscle injury. When you exercise a muscle that is unaccustomed to a particular workload (beginning a new program, or changing the intensity of your current program), muscle damage occurs.

- Some experts believe pain is also

associated with general inflammation and the increased

release of certain enzymes.

- The soreness is not caused by a build up of lactic acid. This is a common misconception that has been disproven by many studies.

- Exercises that stretch or elongate muscles, referred to as an eccentric contraction, tend to cause more damage and soreness than exercises that shorten muscles, called concentric.

- As the body repairs itself muscle fibers become a little stronger to prepare for their next bout of exercise, and soreness is less common.

- How Can I Spell Relief?

- DOMS is often a yellow (caution) flag

that overload is too great. Thus, the most effective way to

reduce DOMS is through quality training habits.

- No more than 10% increases in intensity, resistance, or duration is the best way to minimize muscle soreness.

- There is no reliable evidence that traditional R.I.C.E. therapy (Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation) are effective tools against DOMS.

- DOMS is often a yellow (caution) flag

that overload is too great. Thus, the most effective way to

reduce DOMS is through quality training habits.

- There are 1,440 minutes in every day.

- Parks with paved trails are 26 times more likely to be used for physical activity than those without.

- The percentage of adults who get enough physical activity is 15% higher in neighborhoods that have sidewalks than it is in those that don't.

- Teens are 50% less likely to have a recreational facility near home if they live in a poor or mostly minority neighborhood.

- Teens who are active at school or play sports are 20% more likely to earn an "A" in math or English than sedentary teens.

- Children who live near heavy traffic will have a 5% increase in BMI

- Percent of adults 18 years of age and over who met the Physical Activity Guidelines for aerobic physical activity: 46.9% (2010)

- Percent of adults 18 years of age and over who met the Physical Activity Guidelines for muscle-strengthening physical activity: 24.0% (2010)

- Percent of adults 18 years of age and over who met the Physical Activity Guidelines for both aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activity: 20.4% (2010)

- 37% of adults report they are not physically active. Only 3 in 10 adults get the recommended amount of physical activity.

- 41 million Americans are estimated to have pre-diabetes. Most people with pre-diabetes develop type 2 diabetes within 10 years, unless they make changes to their diet and physical activity that results in a loss of about 5-7 percent of their body weight.

- Walking to and from public transit satisfies the daily physical activity recommendation for 29% of transit users.

- States spend just 1.6% of their federal transportation dollars on bicycling and walking. This amounts to just $2.17 per capita

| Know Your Numbers |

|

Fitness tests or assessments are a great way to check your

fitness levels at the beginning of a new workout program. They also

help track progress and determine if changes need to be made to your

workout routine along the way.

Fitness tests or assessments are a great way to check your

fitness levels at the beginning of a new workout program. They also

help track progress and determine if changes need to be made to your

workout routine along the way.

- Stop by the front desk of your local fitness club or campus fitness center and ask them to assess your baseline fitness levels.

- In addition, here are a few simple fitness tests you can do on your own at home.

Important: These assessments can be considered strenuous. It is strongly recommended that you contact your healthcare provider prior to performing these tests.

- Blood Pressure:

- Self check available at most pharmacies, home unit, or your campus fitness center.

- BMI (Body Mass Index) or Body Composition Test:

- You will need your height and weight, then click here.

- Contact a Fitness Professional on your college campus for a body composition test.

- 12 Minute Walk or Run (to measure the distance

traveled, walk or run, in a 12 minute time period)

- You'll need an accurate watch or timing device to time 12 minutes.

- You'll need a track with clearly marked distance.

- Always warm Up (10 minutes) to prepare your body for the test.

- For the test, walk or run as far as you can in a 12 minute period.

- Record your distance and click here,

- Pushup Test:

- Always warm Up (10 minutes) to prepare your body for the test.

- Begin in a push up position on hands and toes' hands shoulder-width apart; arms (elbows) fully extended.

- Standard Pushup Position:

- While keeping toes, hips, and shoulders in a straight line, lower your upper body so your elbows bend to 90 degrees.

- Push back up to the start position

- Continue with this form and complete as many repetitions as possible - counting each repetition.

- Record the total number of full push ups completed and click here.

- Modified Push Up Position:

- A modified version of the pushup test is used for women, who tend to have less relative upper body strength than men.

- Follow instructions above, participants contact ground with knees instead of toes.

| Thoughts for Living |

|

|

|

|

|

|